Maastricht Art & Icons Walk with TEFAF

Maastricht has a rich history and is home to a wealth of art treasures and architectural gems. Perhaps you are already familiar with many of them, but we are confident that we will still be able to impress you with undiscovered corners of our cultural city.

On the Art & Icons Walk with TEFAF, we meander through the streets of Maastricht and invite …

Maastricht has a rich history and is home to a wealth of art treasures and architectural gems. Perhaps you are already familiar with many of them, but we are confident that we will still be able to impress you with undiscovered corners of our cultural city.

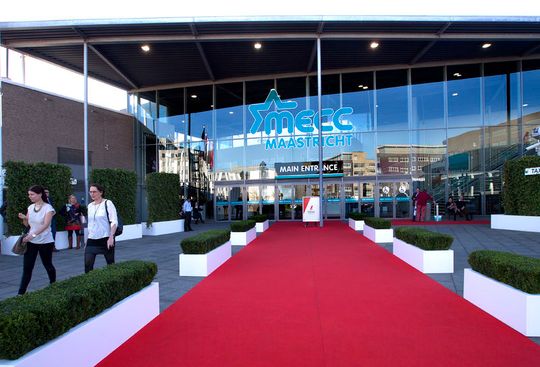

On the Art & Icons Walk with TEFAF, we meander through the streets of Maastricht and invite you to stop and take a closer look at the works of art that grace our public spaces and at the historic buildings that continue to be of value, even after all these years, and have countless stories to tell. And there are also plenty of buildings constructed and designed by famous master builders and architects to admire. Quite fittingly, our route starts at the MECC, home of TEFAF. But the great thing is that you can actually jump in whenever and wherever you want; start at a number of your choice and follow the route from there. Enjoy!

Sights on this route

Gouvernement aan de Maas - Provinciehuis

Limburglaan 106229 GA Maastricht

Natural History Museum

Natuurhistorisch Museum MaastrichtDe Bosquetplein 7

6211 KJ Maastricht

Treasury of St Servatius’ Basilica

Keizer Karelplein 46211 TC Maastricht

Marres, House for Contemporary Culture

Capucijnenstraat 986211 RT Maastricht

Derlon Hotel Maastricht

StokstraatkwartierOnze Lieve Vrouweplein 6

6211 HD Maastricht

St Servatius Bridge (Sint Servaasbrug)

Sint Servaasbrug6221 ES Maastricht

Maastricht’s Train Station Building

Stationsplein 276221 BT Maastricht

Directions

- Vertical elements | Forum 100

Outside the entrance to the MECC conference centre are five vertical bronze elements, designed by Piet Killaars in 1988. Killaars’ work is characterized by figurative geometry, which draws on the unequivocal laws of nature.

However, he produced his first works of art in ceramic. Between 1943 and late 1944, he went into hiding, first in Echt and later in Tegelen. After the liberation of the Netherlands, he travelled around and worked with various sculptors in the Netherlands and Belgium. In 1948, he left for France to study, where he encountered the work of sculptors such as Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Laurens, Germaine Richier, and Alberto Giacometti. After that, he continued to train as a sculptor at the Jan van Eyck Academie under Oscar Jespers (1887-1970). He graduated cum laude in 1953. From 1967 to 1970, he taught spatial design at the Academy of Visual and Architectural Arts in Tilburg, and from 1970 to 1986 he taught sculpture at the Maastricht Academy of Fine Arts.

Killaars was awarded a knighthood in the Order of the Dutch Lion, and he was a holder of the provincial medal of honour of Limburg and an honorary citizen of the city of Maastricht.

Read more about the MECC.

- Provincial Government building / Maastricht Treaty | Limburglaan 10

The Maastricht Treaty (1992) is one of the landmark treaties in the history of Europe and European integration. With this Treaty, the twelve Member States of what was then the European Community founded the European Union – a union that paved the way for deepening, broadening, and streamlining European cooperation.

The Treaty was agreed during the summit of European Community leaders held in Maastricht on 9 and 10 December 1991 (also called the Euro Summit), and it was signed on 7 February 1992 in the Provincial Government building. In conjunction with the Treaty of Rome (1957), the Maastricht Treaty constitutes the foundation of today’s European Union.

The Maastricht Treaty displayed here in the Provincial Government building as part of the permanent collection is a replica. The real Treaty is kept safe in a vault in Italy.

Read more about the Provincial Government building.

- Stars of Europe | Avenue Ceramique 300

To mark the tenth anniversary of the Maastricht Treaty, the artwork ‘Stars of Europe’ was erected in 2001; it was conceived by the Italian artist Maura Biava, who graduated from the Rijksacademie in Amsterdam in 1999. The original idea was to create a virtual monument, but the commissioners (the Municipality of Maastricht and the Province of Limburg) wanted a ‘tangible’ work of art instead. As such, Dutch architect and designer Ruby van den Munckhof gave shape to Maura Biava’s idea.

Ruby van den Munckhof sought to create a light and transparent work of art. ‘Stars of Europe’ consists of 35 aluminium stars; the twelve larger stars represent the countries that made up the original European Economic Community until 1991. The 23 smaller stars represent the new member states that have joined since the signing of the Maastricht Treaty and the formation of the European Union, and those still to join in the future.

Each of the 35 stars sits atop its own aluminium pole; the length of the poles varies from three to fourteen metres. The stars rotate in the wind and, in the words of Biava, are therefore as flexible as the EU. She also often likens the design to a cake full of candles.

- The Bonnefantenmuseum | Avenue Ceramique 250

The Bonnefantenmuseum is situated along the bank of the river Meuse in a suburb of Maastricht, which was historically connected to the city by the Roman bridge to which Maastricht owes its name: Traiectum ad Mosam. The museum building comprises three structures. The central structure is a cylindrical building topped by a high dome, which is crowned by a belvedere, or panoramic platform, from which visitors can admire the view of the river and the city beyond. A long staircase lined with wood transects the central wing. These and other elements constitute the original architectural core, which is reminiscent of the maritime tradition of Dutch cities and the great river that flows through Maastricht and across Europe, as described by Aldo Rossi himself in July 1991.

The Hours of the Day is a work of art created in 1990 by the American minimalist Richard Serra (1938) in the Dutch city of Maastricht. By installing the sculpture in one of the Bonnefantenmuseum’s open courtyards, not only is it a museum piece, but it is also a sculpture in a public space. For the average person, it is not possible to observe the entire piece by simply walking between the panels due to the height of the tallest elements. As you walk around, you become conscious of regularities in distance and height. The longer you spend in the work of art, the more you become aware of the space.

At the Bonnefantenmuseum you will find ‘old’ art dating from the period between 1100 and 1800, modern and contemporary art, but also craftwork; silver and pottery, a rich selection of pieces by Aldo Rossi and, of course, changing temporary exhibitions.

Click here for more information about the Bonnefantenmuseum.

- Centre Céramique | Avenue Ceramique 50

The iconic city library of Maastricht, which was designed by Jo Coenen, first opened its doors in 1999. The building has been a favourite among locals and tourists from day one. In 2021, Centre Céramique underwent a metamorphosis to accommodate a range of new functions, including providing a home for the Kumulus music school.

This innovative and creative transformation was achieved, in close consultation with the library’s architect, by developing a box-in-box concept, using thick glass walls and heavy steel doors, and by positioning segmented MDF panels in a particular way. The building is a work of art in itself, but there is plenty of history and art to wow visitors throughout the building. For example, a 35-metre-long display case in the central hall presents changing exhibitions of the 57,000-piece Sphinx earthenware collection. The interior of the building is enhanced with surprising designs and objects by well-known artists. Equally remarkable are the Butterfly and Flower by Ine van Helfteren, made from ceramic shards, and the works of famous Dutch poets, which are displayed in unexpected places. The historical model of Maastricht in 1748 is also worth a closer look.

Read more about Centre Céramique.

- Fortress Museum in the Helpoort (Hell’s Gate) | Sint Bernardusstraat 24b

The Helpoort, or Hell’s Gate, is the oldest city gate in the Netherlands and the only one still standing in Maastricht. It was built in April 1229 after Hendrik I, Duke of Brabant, gave his permission for its construction. For about two centuries, the gate was part of the city's fortifications. It lost this function when the Nieuwstad (New City), the area south of the gate, was surrounded by a wall in the second half of the 15th century. It was then used for various purposes: as a meeting place for the cloth fullers and walkers, an armoury, a powder storehouse, and a residence.

The Fortress Museum is located in the oldest city gate in the Netherlands. The monument dates from 1229 and is definitely worth a visit. In true medieval style, the entrance is hidden on a small square next to the gate, and inside you will find a fascinating exhibition. In the Fortress Museum, you will find real evidence of its illustrious history, so be sure to come and have a look!

Read more about the Helpoort.

- Limburg Regional History Centre, ‘crack in the wall’ | Sint Pieterstraat 7

It is impossible to miss the gigantic ‘crack in the wall’ in the monumental building of the Limburg Regional History Centre. It looks as though the stone window frames could fall down at any minute, were it not for the fact that the lower one is still anchored to the building on one side. The crack was created during major renovation works at the National Archives in 1994, and many people were against it at first. It has since become a permanent feature of the street.

The crack offers a glimpse into the historical activities that take place in the building, and the Latin proverb – NON SUM QUALIS ERAM, I am not what I used to be – – provides food for thought. Is this proverb about the building, perhaps? After all, the crack is relatively new, and the entire façade has already had several faces. Or is it about the archives, or perhaps even the onlookers themselves? Some stay a little longer, others walk on after having a quick look.

- Monument to d’Artagnan | Aldenhofpark 4-5

On 25 June 1673, the legendary d'Artagnan died in a bloody battle between French and Dutch State’s troops near the Tongeren Gate in Maastricht. A bronze statue was unveiled in 1977 on the very spot where this musketeer captain was killed. The statue was designed by the sculptor Alexander Taratynov. D’Artagnan's full name is Charles Debatz-Castelmore. The honour of unveiling the statue fell to the then councillor Debats, who, incidentally, was not related to the count.

D’Artagnan became widely known through the writer Alexandre Dumas, who wrote about the adventures of three musketeers, members of the Royal French Guard.

Take a seat on the semi-circular bench and admire the beauty this part of the city park has to offer.

- Passage to Wisdom | Grote Looierstraat 17

Commissioned by Maastricht University’s Art and Heritage Committee, the late Bořek Šípek created ‘Passage to Wisdom’, the entrance to the university library on Grote Looiersgracht in the old city centre of Maastricht.

The modern gateway made of glass and steel connects the building with the street and passers-by, creating a sense of openness. In the words of the artist himself, ‘Passage to Wisdom’ is not only practical, but it also has aesthetic value.

Bořek Šípek was a prominent Czech architect and designer. He was known for his individual, unconventional, colourful, and rich style. He experimented with unexpected and often opulent forms. He is particularly well known for his glass sculptures.

- Natural History Museum | De Bosquetplein 7

The Natural History Museum of Maastricht is located in the former Grauwzusters cloister in the Jekerkwartier. The museum is well known for its unique collection of fossils from the Cretaceous period, including various Mosasaurs, Prognathodons, and Hadrosaurs.

Travel back in time to the Carboniferous period and see the giant Mosasaurus fossil that lived here in the Cretaceous sea and the aquarium with local wild fish species. See the animals of the forested hillsides, the chalk grasslands, and the gravel pit pools; or check out the older section of the museum. The ‘dynamics’ exhibit illustrates the interactions between humans and nature. You can also see inside a real beehive with buzzing bees.

Read more about the Natural History Museum.

- Jan van Eyck Academie | Academieplein 1

The Jan van Eyck Academie is an international post-academic institute for the visual arts. It is located in a building that dates from the late ‘50s/early ‘60s, designed by architect Frits Peutz, and is a municipal monument. The Academie offers residencies to visual artists, designers, architects, curators, poets, and writers. At the Jan van Eyck Academie / Margaret van Eyck Academie, they are given the space and time to develop their talents. The Van Eyck has a number of workshops for technical experiments using various materials and techniques. Around forty artists work at the Academie each year, and they may be engaged in the fields of visual arts, woodwork and metalwork, film, video and photography, or writing and poetry.

Jan Van Eyck (circa 1390-1441) was court painter to the Burgundian duke Philip the Good (1396-1467). The flamboyant duke and his companions surrounded themselves with the best artists.

- Fotomuseum aan het Vrijthof (Museum of Photography on Vrijthof Square) | Vrijthof 18

Fotomuseum aan het Vrijthof is a private photography museum located in the centre of Maastricht. The photography museum is situated in the former Spaans Gouvernement building (Spanish Government), which served as the external palace of Emperor Charles V as early as the 16th century. It is probably the oldest preserved residential building in Maastricht. Following several major restorations, the building was transformed into what we now know as the Fotomuseum aan het Vrijthof. The theme that connects all exhibitions held at the photography museum is social relevance. It offers a space for experimentation, both online and offline, and new crossovers within the cultural sector. At this museum, visitors are welcomed with traditional Limburg hospitality and are treated in an interesting way to engaging experiences and exciting cross-pollinations in an intriguing setting.

Read more about Fotomuseum aan het Vrijthof.

- The crypt of St Servatius’ Basilica | Keizer Karelplein 3

The shrine of St Servatius, also referred to as the Noodkist (literally: calamity coffin, a reference to the belief that it could help avert or resolve calamities), is the most valuable shrine and contains the relics of the Netherlands’ first bishop. It is a beautiful example of ‘Maaslands’ goldsmith craftsmanship, which is still carried through the streets of Maastricht every seven years during the Procession of Holy Relics.

In the basilica’s crypt, you can also admire the goblet and the bust of St Servatius as well as objects that are attributed to the city patron, such as the bishop’s staff, the pectoral cross, the pilgrim’s staff, and the key. A rich collection of reliquaries in precious metal and ivory is displayed around these objects. You can also marvel at the unique collection of silk fabrics from the sixth century onwards, as well as the many paintings and sculptures.

- Theater aan het Vrijthof (Theatre on Vrijthof Square) | Vrijthof 47

From palace (undefended royal residence) to monastery to General’s House to theatre. In 1914, the building was sold to the Municipality of Maastricht. It was successively home to the municipal museum, the municipal collector, the city archives, the city library, and the municipal police.

It is debatable when the Theater aan het Vrijthof was actually founded. Four dates are in contention: 1948, 1978, 1981, and 1989. In 1948, the monthly magazine Kunstschouw was launched, which presented itself as the official publication of the Maastricht City Theatre, the Maastricht City Orchestra, and the Maastricht Arts Society. The second possible date is 1978. In that year, the multi-year plan that was presented to Maastricht’s city council included a considerable ‘reserve’ for a new venue for musical performances. On 15 August 1981, ‘the realization of a music hall in and behind the General’s House’ was given the green light.

On 13 May 1985, restoration works on the General’s House began, and in 1987 the plan was presented to the city council to convert the music hall on Vrijthof Square into a theatre. And so the name Theater aan het Vrijthof was born, ‘a name that rings and sings’, as mayor Houben put it at the time. On 13 December 1989, work officially started on the conversion of the theatre. The theatre was built behind the General’s House, based on a design by Arno Meijs, who also designed several theatres for Joop van den Ende.

Read more about the Theater aan het Vrijthof.

- Marres | Capucijnenstraat 98

From its historic home in the centre of Maastricht, Marres explores contemporary art in the broadest sense of the word. The museum was founded in 1998 and owes its name to the Marres brewing family, who lived in the house in the 20th century.

Marres develops exhibitions, organizes workshops, releases unique publications, creates walks through the city and the wider region, and offers a wide range of educational and participation activities. Marres’ programme revolves around experience and emphasizes the mechanics of the senses and the language of the body. To achieve this, Marres collaborates with makers from various disciplines: visual artists, musicians, theatre makers, dancers, scientists, but also perfumers and chefs.

Through its internationally oriented programme for artists and the public alike, Marres builds bridges between the world of contemporary art and everyday experience from its intimate location. Next to the museum, in the same building, you will also find the Mediterranean restaurant Marres Kitchen with a beautiful public city garden at the back.

Read more about Marres.

- Dominicanen | Dominicanenkerkstraat 1

Since the autumn of 2006, you can find the unique Dominicanen bookshop (previously Selexyz Dominicanen and Polare Maastricht) in the centuries-old Dominicanenkerk (Dominican church). Two hundred years ago, the church lost its sacred function and has since served for many years as a reptile house, bicycle shed, and ‘carnival temple’. Many Maastricht residents have special memories here, including their ‘first kiss’ at carnival time. You can still feel this rich history at this beautiful location. The seven-hundred-year-old cathedral with its unique and contemporary function oozes atmosphere, and the high Gothic arches create a sense of spaciousness and tranquillity while browsing the books.

Dominicanen bookshop has a wide range of public books, music, and books for professionals. Yet as this place even attracts those who are not so much interested in books, it is a must-see location if you are in Maastricht. In the Dominicanenkerk’s former choir, you can enjoy a delicious cappuccino or lunch provided by the famous Blanche Dael Coffeelovers (Maastricht’s ultimate roasting house). Dominicanen bookshop also serves as a cultural venue, with regular lectures, debates, and music performances and even an exhibition space. A walk through the Dominicanenkerk is an experience in itself: it’s no wonder it’s called the most beautiful bookshop in the world!

- Sphinxpassage | Sphinxcour

The Sphinxpassage is a 120-metre-long tiled and covered passageway connecting the Eiffel building with the Pathé cinema. Nearly 30,000 tiles bring to life the history of Sphinx together with words, images, and objects. In the area surrounding the Eiffel building, the Sphinxkwartier is rapidly transforming into a modern, vibrant city district. The Eiffel building has been restored, and The Student Hotel has been occupying a large part of the building since September 2017. In 2018, the Eiffel building underwent further development to accommodate new functions for living, working, and retail. However, the past has not been forgotten: the opening of the Sphinxpassage has secured a place for the rich history of the area.

The Sphinxpassage tells the story of Sphinx and Maastricht’s ceramic industry in 26 chapters featuring tile tableaus of family portraits, factory buildings, tableware decorations, old advertisements, and toilet bowls. Each tableau is accompanied by a background story (in Dutch and English), written by historians Jac van den Boogaard and Paul Arnold.

Read more about Sphinxpassage.

- Bureau Europa | Boschstraat 9

Bureau Europa is a platform for architecture and design and it organizes exhibitions. It is the venue for lectures, workshops, city tours, and a range of other activities about architecture, urban planning, and design. It strives to make a contribution to society and to promote talent development and knowledge production against the backdrop of a shared European and Euregional social agenda.

Bureau Europa is dedicated to telling new stories about cities, design, and our surroundings. You can expect to discover contemporary exhibitions that, for example, speculate on depictions of ‘the end of time’, bringing together the works and stories of artists, architects, designers, and scientists, each offering their own perspective. Bureau Europa also offers a platform for talented local musicians. And if you are in the mood for a city tour with a twist, be sure to join one of Bureau Europa’s walking tours and discover the city in a unique way.

Bureau Europa provokes and inspires reflection on the times in which we live, our surroundings, and the future that lies ahead.

Read more about Bureau Europa.

In its role as a platform and network organization, Bureau Europa organizes exhibitions, lectures, workshops, city tours, and other discursive activities related to architecture, urbanism, and design. In line with its desire to contribute to society, Bureau Europa promotes knowledge production and talent development in the cultural field. These ambitions manifest themselves in cultural projects organized both within the institute and in the public realm. Bureau Europa’s endeavours are primarily centred around the shared European social agenda and that of the Meuse-Rhine Euregio.

Through its programme, Bureau Europa aspires to trigger and broaden the analysis of the designed environment through partnerships and projects that tell new stories about our cities, design, and surroundings. This institution focuses its attention primarily on Europe and the Euregio, whilst never losing sight of international trends.

- Muziekgieterij | Boschstraat 5

The Muziekgieterij concert venue is committed to providing a robust foundation for the music scene in Maastricht, and the Euregio, that is accessible to everyone. From pop-rock to indie and urban, and from emerging singers to well-known bands – Muziekgieterij is driven by a passion for music.

Muziekgieterij is one of the newest concert venues in the Netherlands. It was founded in 2004, and in less than 20 years it has evolved into one of Maastricht’s and the Euregio’s musical trendsetters.

Muziekgieterij is located in the former timber factory. The factory buildings were once part of the Koninklijke Sphinx’s crystal and earthenware factory and consisted of workshops, warehouses, a showroom, and a power station. When the timber factory closed down, the decision was made to convert it into a cultural centre. The building is currently home to Muziekgieterij and Lumière cinema.

Read more about the Muziekgieterij.

- Lumière | Bassin 88

Since September 2016, the Lumière cinema has been housed in a beautiful new building in the Sphinxkwartier. This national monument was built in 1910 and functioned as a power plant for the manufacturing industry in the Sphinxkwartier. The original atmosphere of the power plant – now serving as a restaurant and café – has been preserved through the use of original materials and objects.

Lumière has a long tradition of showing alternative films. Lumière was established in 1976 as ‘Stichting Filmhuis Maastricht’, making it part of a national movement: at that time, spurred on by the International Film Festival Rotterdam (then known as ‘Film International’), an arthouse cinema was opened in just about every large Dutch city. In 1983, Lumière attracted 7,000 visitors; by 1985 that number had risen to 16,000. Stichting Filmhuis Maastricht then moved to the location on Bogaardenstraat. It was during this period that the name Lumière was born – the cinema was named after the Lumière brothers, the founders of cinema.

Ever since those days, Lumière has continued to grow. In 1996 (30,000 visitors), a third auditorium was added and in 2004, the capacity doubled to 336 seats, spread across six auditoriums. Since then, visitor numbers have soared from 45,000 to over 100,000 per year. September 2016 witnessed the next big milestone for the cinema: the relocation to its new (and current) home at ‘t Bassin.

Read more about Lumière.

- Minckelers and the flame | Markt

Jan Pieter Minckelers was born in Maastricht in 1748. His grandfather was a doctor, and his father owned a pharmacy on Herenstraat. Like many sons of the wealthy middle classes, he was educated by the Jesuits, close to the family home. In 1764, he continued his studies in Leuven, after which he became a deacon.

He was a Dutch physicist and pharmacist; he studied natural sciences at the University of Leuven, where he was appointed professor in 1771. On 1 October 1781, he (in collaboration with Van Bochaute) discovered what he called ‘inflammable air’ by heating crushed coal. On 21 November 1783, the first balloon filled with this gas took off from the park of the castle in Heverlee near Leuven; it landed 25 kilometres further on in Zichen. As early as 1785, Minckelers regularly illuminated his lecture hall with the gas lamp he had invented.

In 1789, he returned to his hometown, where he made his living as a pharmacist. He was also interested in meteorology, geology, and palaeontology. Cuvier even used his description of the bones of the Mosasaurus fossil.

He subsequently taught physics and chemistry at the Ecole Centrale in Maastricht, which had been founded by the French. From 1801 to 1815, Minckelers was a member of the local council in Maastricht. In 1816, he joined the Academy of Science in Brussels. Shortly afterwards, he suffered a stroke; he died on 4 July 1824 at the age of 76.

In 1902, a committee was formed to erect a memorial to this distinguished man from Maastricht. The statue that you can see on the Markt today (Boschstraat) was designed by Bart van Hove from Amsterdam and cast in bronze by the Breussel-based firm Verbeyst. With his invention, Jan Pieter Minckelers was one of the pioneers of the many applications of gas that we still benefit from today. An eternal flame symbolically burns from the gas pipe he is holding in the statue.

- Stadhuis (City Hall) | Markt 78

City Hall on Markt square was built between 1659-1664, under the supervision of architect Pieter Post. The tower dates from 1684 and contains a carillon with 49 bells, which are sounded regularly. The interior is also very attractive, with beautiful wall tapestries, stucco work, ceiling paintings, and mantelpieces. The City Hall’s basement is where the prisons used to be, and the vaulted rooms on the ground floor – once used to store the malt scales and the fat scales – are now home to the information centre. The mayor’s office and three more meeting rooms are also located on this floor. A meeting place has been created in the centre of the ground floor. In 1695, a pillory and a ‘draeyhuysken’ (a wooden cage that can be turned) were erected next to the double staircase at the front of the building, so that punishments could be served here. In 1757, wrought-iron gates – which we can still see today – were erected around them. In those days, people sentenced to death were also executed in front of the City Hall; the last time this happened was in 1860.

Read more about the virtual tour of the City Hall.

- Dinghuis | Kleine staat 1

The Maastricht Visitor Center is located in the Dinghuis in Maastricht, a building with a long and illustrious history. The name comes from the Dutch ‘dingen’, which means ‘to administer judgement’. Even these days, we still talk about a ‘geding’ (Dutch for legal proceedings). The building dates from 1470. In the Middle Ages, it housed two courts: one for Brabant and one for Liège. At the time, Maastricht was partly governed by the Duke of Brabant and partly by the prince-bishop of Liege. In 1664, the courts relocated to the new city hall on Markt square.

The Dinghuis immediately catches the eye; it towers over the surrounding buildings and dominates Kleine Staat and Grote Staat. The late-Gothic façade is constructed from grey freestone. The windows are decorated with three coats of arms: those of the Duke of Brabant, the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, and the City of Maastricht. A double staircase leads to the entrance on the first floor. The original staircase was adorned with two bronze lions, which disappeared during the Iconoclastic Fury in 1566.The staircase itself was removed during renovation works in 1749 and restored in 1912.

Read more about the Dinghuis.

- Basilica of Our Lady | Onze Lieve Vrouweplein 7

The spot where the Basilica of Our Lady now stands was the site of a small church as early as the fifth century AD. This was probably the oldest Christian church in the Netherlands and may have been built on top of the remains of a Roman temple. The base of the westwork houses two enormous stones that originate from the Roman fortress. The Basilica of Our Lady, or ‘slevrouwe’ (Our Lady) as it also known by the locals, is a fine example of Romanesque architecture. Several exceptional works of art can be found in the church. The crypt also has a large number of objects of ecclesiastical art and crafts such as luxuriously embroidered copes and chasubles, the ‘Levite Dress’ of St Lambert (Maastricht’s last bishop), relics in ornate reliquaries, procession banners, and religious silver objects and statues.

Both religious and non-religious visitors and residents often light a candle in reverence. The candles cast mesmerizing reflections on the glass behind which Mary shines bright. It is a beautiful sight and definitely worth a visit, whether as a one off or as a ritual!

- Roman cellar at Derlon Hotel | Onze Lieve Vrouweplein 6

Situated on the most beautiful square in Maastricht, Onze Lieve Vrouweplein, you will find Derlon Hotel. Guests have been coming here to revel in the style and enjoy the exclusive culinary delights for 150 years. This building has a rich history that dates back 2,000 years; and a visit to the cellar reveals all. In the atmospheric museum cellar of Derlon Hotel, the remains of Roman civilization in Maastricht are literally at your feet. This is an ideal opportunity to admire the extensive archaeological excavations. The first excavations you will see are from the late Roman period: immensely thick walls were part of the castellum (the defences). Further on, you will find the remains of a Roman sanctuary.

You will be able to spot sections of a gate and a column, among other things. Travellers on the Via Belgica would bring their sacrifices here to ensure a safe journey or lucrative commercial dealings. The well suggests that it was also a resting place along the road. The oldest excavation is right at the bottom of the site: a pre-Roman (probably Celtic) road paved with Maas cobblestones. This road was used more than 2,000 years ago.

Read more about Derlon Hotel Maastricht.

- Amazon on horseback | Op de Thermen square

Artist Arthur Spronken (1930-2018) is regarded as the forefather of sculptors in Limburg. He was a small man who made big sculptures – impressive sculptures, though he never blew his own trumpet. In his youth, Spronken was influenced both by his father’s and grandfather’s love of horses and by the sculptor Paul Schmalbach. He trained as a trader, but in the end attended the Kunstnijverheidsschool (School of Applied Arts) in Maastricht, where he was taught by Charles Vos and Harry Koolen, among others. Arthur Spronken’s horse torsos reveal the dynamic of the body. This dynamic becomes such a significant aspect in his later horse torsos that he only depicts the initial thrust of the legs, the beginnings of the movement that takes place in the torso. Although the horse became a recurring element in his oeuvre from 1962 onwards, his works do not depict a realistic horse. Spronken focused exclusively on the horse torso; he depicts nothing more than the body, the buttocks, and the neck.

- Mestreechter Geis (The Spirit of Maastricht) | Het Bat

The character of the people of Maastricht, the Mestreechter Geis, has been shaped by a long history encompassing many influences from beyond the city’s walls. Nobody can capture this character in a single definition, but words not indigenous to this character can best describe it as follows: a certain nonchalance, Weltschmerz, laissez-faire, and a stiff upper lip!

The how and why of this statue, inspired by Arlequino of the Comedia dell'arte, can be found around the statue in the form of facts written on the foundation stone, the characters in the cosy cafés...

The sculpture was made by Haarlem-born artist Mari Andriessen. It is a playful, charming, graceful, Burgundian figure – characteristics that still typify the average Maastricht native. The statue is about 1.30 metres high and was unveiled in the spring of 1962.

In April and May 1966, riots were commonplace in the 'het Bat' street and Stokstraatkwartier neighbourhood of the city, instigated by young people in Maastricht. On 30 April 1966, the statue, which was damaged in the riots, was removed for safety reasons and stored on the grounds of the Public Works in Limmel, where it was stolen on 29 November 1966. On 4 February 1967, during the Carnival celebrations, the Mestreechter Geis was returned to its original place.

- St Servatius Bridge (Sint Servaasbrug)

This is the oldest bridge in the Netherlands... but not in Maastricht. South of St Servatius Bridge, on the eastern river bank, stands a pillar with a lion’s head indicating where a Roman bridge previously was. St Servatius Bridge replaced that Roman bridge and has since been redesigned, renovated, bombed, detonated, and rebuilt. Even so, it remains the same at its core!

A wooden arch on the Wyck side of the Meuse was demolished in wartime, after which the stone replacement was blown up. Ultimately, steel parts of the bridge were detonated in 1940 and 1944. So, it is safe to say that the St Servatius Bridge has certainly been through quite an ordeal.

The current steel section of the bridge is a vertical-lift bridge that can accommodate large inland vessels. As this process is controlled remotely, the bridge keeper’s house (tower) has been renovated to house artwork.

- Maastricht’s Train Station Building | Stationsplein 27

At the end of 2021, following more than two and a half years of restoration works, Maastricht’s train station was restored to its former glory, including the return of historic elements from the monumental building. The station first opened in 1916 and was designed by George van Heukelom. The platform roof made from reinforced concrete is characteristic of major technical – and, therefore, innovative – developments in that era.

The station’s historical elements have been restored and exposed once again, such as the large mural in the AH to go, the original fountain in the station hall, and an old station clock. The building’s façades have also been cleaned, and the authentic Mosa floor and wall tiles have been restored.

At the station, you can scan the QR codes at the ‘Station’s hidden treasures’ to discover and learn more about this remarkable building.

EXTRA TIP: Zonneberg Caves | Slavante 1

Deep in the Zonneberg caves you will find a museum carved out of marl and filled with extraordinary treasures. During a guided tour, the tour guide takes you on a fascinating journey into this underground world. Brace yourself for a long walk, guided by the unique charcoal drawings in the cave. Along the way, the tour guide shares amazing stories about the first tours that were given here in the early 1900s. The highlight, of course, is the ‘museum’ from those days. In the ‘museum’, you will come face to face with a metres-long Mosasaurus carved in marl, and you can admire the full-scale Night Watch in charcoal. And there are plenty of other pieces to capture the imagination as well!

Read more about the Zonneberg Caves.

Maastricht’s Train Station Building

Stationsplein 276221 BT Maastricht